Ed: Keeping a community healthy starts a long time before a medical degree can be employed. Public Health physician Dr Bret Hart explains.

Shit Life Syndrome (SLS) might have been my diagnosis had I known of it all those years ago. Instead, I am ashamed to admit, I used a term which was prevalent at the time to account for my many patients with psychosomatic symptoms; “supratentorial” i.e. it’s all in your head.

Had I used a diagnosis conceived irreverently in jest, I would have done so without realising it would ultimately be taken seriously as being potentially deadly.

The term SLS was first coined by US family physician Dr Doug Farrago in 2001 in the first issue of his Placebo Journal – the MAD magazine of medicine. Nearly a decade later, a GP in North England thought he had discovered a new syndrome describing an unemployed mother with an abusive boyfriend and a young baby to feed coming to the GP because she “…felt shit …and didn’t know what else to do.” He concluded she had low mood caused by adverse life circumstances – “…otherwise known as SLS.”

Had he referred her to a mental health service, she wouldn’t have been accepted. In 2013 (by which time SLS was part of the medical lexicon in the UK) a mental health service intake meeting decided it was inappropriate to accept patients referred with SLS.

A professor of psychoanalytic psychotherapy analysed the team’s response and deduced that their empathy was comparable to that applied to their own waste products and yet “… the organization … is confronted by continual pressure from the public and from referrers to provide psychological care and treatment for these same individuals who arouse such intense anxiety and from whom its staff wish to distance themselves.”

Despite its derogatory connotations, a redeeming feature of SLS is that it should prompt examination of the socioeconomic circumstances in which SLS ‘patients’ were born and where they grew up, live, work and age.

If these circumstances – which constitute the social determinants of health (SDoH) – are ‘shitty’, the patient’s health is at risk.

This is well illustrated in an award winning analysis in the Financial Times – see www.ft.com/blackpool. SLS is also blamed by political economist and Hertford College Principal Will Hutton for stopping the longstanding improvement in life expectancy in the UK and USA (and maybe Ireland).

Australia’s improving life expectancy is also slowing. In the MJA earlier this year, Lopez finds this “difficult to explain” especially as it’s occurring more than other high income countries. He says it will be difficult to further reduce mortality from ischaemic heart disease, cerebrovascular diseases, and cancer so “…future gains in life expectancy will increasingly depend on controlling other risk factors”. Is one of those risk factors SLS?

Arguably SLS arrived and was discovered in WA in 1990 by Professor D’Arcy Holman. He conducted a review of Community Child Health services and discovered that staff “…felt under siege from the community demand for pastoral care, counselling and social welfare services…to render assistance to persons suffering from psychosocial morbidity (PSM).” His definition of the latter could apply to SLS – “a state of human distress resulting from personal conflict within …an individual, and/or from an adverse social environment.” Holman indicated that the perception (but not evidence) was that “…the need and demand for human services staff to render assistance to persons suffering from PSM had greatly increased since the late 1970s…”

In response, he suggested a community debate on “family, work and personal wellbeing.” It did not happen so it’s long overdue. Also none of Holman’s 172 recommendations were implemented to enhance community child health with a legacy being felt today.

Surprisingly no one seems to have considered the impact on children of SLS despite the substantial evidence from the Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACE) studies showing that a toxic social environment has profound effects. By combining ACE with SLS you have a perfect pathogenic storm. This particularly applies to the First Nations People and helps explain the challenge in bridging the gap in life expectancy.

The Sustainable Health Review (SHR) indicated “the WA health system cannot hope to improve the SDoH on its own”. If the circumstances which constitute the SDoH lead to SLS, there is a need to respond to Hutton’s call for a “multipronged assault on SLS and the conditions that cause so many to die prematurely.” As a whole of government response is required, this is an opportunity for Premier and Cabinet to lead a taskforce to mount that “assault” and thereby realise “… a vision for the future that is shared with the community, [which…] will be key to supporting people in their pursuit of healthier, more active lives” – to quote the SHR again.

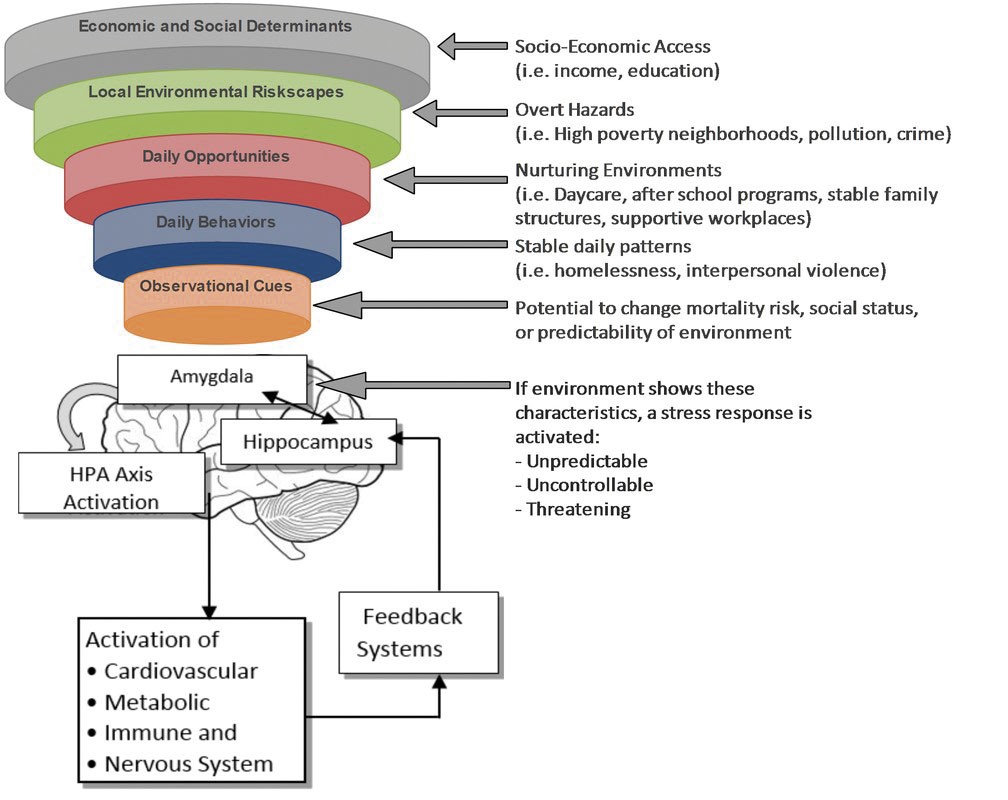

Clearly SLS is not PC. Following the concept of, for example, an obesogenic environment, how about Stressogenic Environment Syndrome (SES) as an alternative with levels of influence summarised in the diagram?

ED Medical Forum will be conducting an e-poll in the coming weeks to hear doctors’ experiences with these types of cases and what they would like to see happen.